no images were found

Operated by the state of Georgia’s Department of Natural Resources, Ossabaw Island, Georgia would be the second stay for the Slave Dwelling Project with a high level of bureaucracy, Sweet Briar College in Sweet Briar, Virginia was the first. The nature of the Slave Dwelling Project now dictates that I invite as many other people to join me in the stay as the dwelling can accommodate. This stay would have a slight variation. To get to the island, one has to catch a boat. Twelve of us would stay on the island on Friday, May 10, three of us in one of the slave cabins and the remainder in a dormitory.

Given only three slots for sleeping in the cabin, I had to choose the two people who would stay with me very carefully. Toni Battle of the Legacy Project chose her spot based on the early release of the project’s 2013 schedule so she knew more than six months ago that her spot was secured. Additionally, for her, travelling from San Francisco would take some intricate planning. The fact that this would be her third stay in a former slave dwelling had her somewhat prepared for what she would experience. Her two other stays were Bacon’s Castle in Surry, Virginia and Sweet Briar College in Sweet Briar, Virginia. The second person who would join me would be author Tony Horwitz. I met Tony over 20 years ago when I was a young Park Ranger at Fort Sumter National Monument. He interviewed me for a book that he was writing titled Confederates in the Attic. He had planned to stay in a slave dwelling with me two months earlier at Hopsewee Plantation in Georgetown, SC but unforeseen circumstances caused him to postpone. Tony is now writing for a major magazine and will do a story on the Slave Dwelling Project. Both Toni Battle and Tony Horwitz flew in to Charleston, SC and we all rode to Savannah, GA together.

Our host Paul Pressly, Director of the Ossabaw Island Education Alliance at Ossabaw Island Foundation, planned the events for the stay well. The formation of a new collaboration between the Pin Point Museum, Ossabaw Island Foundation and Bethesda Academy to tell their respective stories within the framework of the Gullah-Geechee culture dictated that a press conference be held. This event which was held at the Pin Point Heritage Museum, a former oyster and crab factory, was well attended by a wide array of movers and shakers from the Savannah community as well as stake holders in the newly formed collaboration.

Before the press conference, I was introduced to Hanif Haynes whose great, great, great grandfather David Bonds was born into slavery about 1815 at Middle Place on Ossabaw Island. Hanif, who would be spending the night with us on Ossabaw Island, told me the real story of the how the land for the Pin Point Museum was acquired and it was not all pretty. At the press conference, I was happy to share the stage with the illustrious Emory Campbell my former boss when I worked as Director of History and Culture on Penn Center on St. Helena Island, SC. After the press conference, lunch was served at Bethesda Academy which began as a colonial orphanage in 1740 but is now a private, residential and day school for young men in grades six through twelve.

Spending a night at McLeod Plantation on James Island, SC gave me the first opportunity to sleep in a slave dwelling on a sea island. Ossabaw Island, GA would be my second opportunity but it would be the first time that I would have to catch a boat to get there. Ossabaw Island would also give me a better sense of how isolation factored into maintaining the deep traditions of the Gullah Geechee culture and the “Africanisms” that still exists. Ironically, we had to go through a gated community to get to the dock that the boat was located that would transport us. Our first stop upon getting to the island was the dormitory where the nine participants not staying in the cabin would stay. Through an introductory session led by our host Paul Pressly, we all learned about our reasons for being on Ossabaw Island. The session included storytelling by Patt Gunn. Patt did a beautiful job in weaving the Gullah dialect into a story that included how Georgia was settled and the roles that the enslaved played in that process. We then embarked on a walking tour in the direction of the slave cabins. Along the way, we stopped at a smoke house that was made of tabby and got an inspiring lesson from Paul and Hanif on how tabby buildings were constructed.

Three cabins made of tabby still exist on the island. The two front doors on all three cabins were clear indications that they were all designed to house two families. My examination of the first cabin reinforced my fear of having to sleep on a dirt floor. We were slated to sleep in the second cabin which also had a dirt floor but luckily for us the half where we were to sleep that night had a newly restored wood floor. When the group entered the space, I immediately went to the place that I knew I would be laying my sleeping bag for the night. It was there that I described for the group how this former slave dwelling compared to others of which I slept.

We then all loaded onto a truck for a trip to the site of Middle Place and Middle Place Plantation. On our way there the former presence of Native Americans was evident throughout and well interpreted by our host Paul Pressly. At our destination we saw ruins of where the first plantation house was located. While visiting the ruins of one of the slave cabins, we had an encounter with a cottonmouth snake. As I turned around to hold a plant to keep it from brushing back and hitting the people behind me, I noticed the well concealed snake at the base of a tree. In passing, I had stepped within a foot and one half from its location. Rather than panicking and causing everyone else to panic, I emphatically instructed them to pass as close to me as possible. When everyone was clear of the snake, I then told them of its presence and we made a collective decision that we would not be returning on that same path. Someone in the group knowledgeable of snakes identified it as a cottonmouth and although it was coiled they estimated it to be about five feet.

Dinner was served on another part of the island which took us past the home of Mrs. Eleanor Torrey West, her family owned the island during part of the 20th century and she sold it to the state of Georgia with the condition it remain a nature preserve and educational center. She is now 100. Our cook, Mr. Roger Parker, who also cooks on a part time basis for President Jimmy Carter did not disappoint serving up barbeque pork, grilled chicken and all of the fixings. Mr. Parker was the last person to inhabit one of the tabby slave cabins. He told us that he was quite familiar with the cottonmouth snake that we saw on our excursion.

The entire group made its way back to the slave cabin tabby # 2 to conduct a sacred moment of blessing the space. After assembling an altar in the middle of the room which we all encircled and using a term called smudging, Toni Battle released aromatic smoke into each corner of the space with the aid of huge feathers that had fallen from birds on the island. Toni then led us in the pouring of libations with everyone getting an opportunity to call on ancestors of their choosing. We all then proceeded back to the dormitory where various conversations were carried on until midnight.

Featured Gallery: Photos By Jeanne Cyriaque

no images were found

When Toni Battle, Tony Horwitz and I got back to the cabin we laid out our sleeping bags and got comfortable within them. It was evident that Toni Battle was operating on west coast time as Tony Horwitz and I slowly faded into sleep. The following morning it was great to wake up to the sounds of nature and hear nothing that was manmade. Our conversation included opportunities for slaves to escape; the underground railroad running south to Florida; and where we would stay on Saturday night. Tony Horwitz expressed that for the purpose of the story that he would write, sleeping on a dirt floor would have been more compelling. After a hearty breakfast, the group that stayed in the dormitory was transported back to Savannah. Their absence gave Toni, Tony and me the opportunity to use the showers in the facility as we saw fit. This was great because another group was scheduled to come over to the island to interact with us for a few hours. They showed up as planned and, with the exception of spending the night, they were treated to the same program of the previous group. After that repeated routine, we all boarded the boat and returned to Savannah.

Wormsloe Plantation

When Toni Battle, Tony Horwitz and I left Charleston, SC on Friday, May 10, 2013, we knew that we would be staying in a tabby slave cabin on Ossabaw Island, GA that night. We also knew that on Sunday, May 12 that I would address the congregation of Sweetfield of Eden Baptist Church in Pin Point, GA. What we did not know was where we would stay on Saturday night. I had alerted my host Paul Pressly to this concern and he was working on a solution which may have included a hotel stay. Knowing that this was a pending issue, I made a request to the group that showed up for the press conference. During my presentation, after having familiarized the attendees of why the Slave Dwelling Project was necessary and knowing that Savannah like Charleston, SC had many places that qualify, I asked if anyone had a place that fits the criteria of the project that we could stay on Saturday night. Immediately after the press conference was over, Sarah Ross, President of the Wormsloe Institute for Environmental History offered the slave cabin on Wormsloe Plantation for the Saturday night stay. My mind was now at ease knowing that I could proceed to Ossabaw Island not worried about where we all would stay on Saturday night, moreover it was a place that aligned with the intent of the Slave Dwelling Project.

On our way to Wormsloe, Hanif Haynes took us on a detour to see Mr. Herbert Kemp a senior African American community member. Mr. Kemp, who was not expecting us, made us aware that he had read about the newly formed partnership between the Pin Point Museum, Ossabaw Island Foundation and Bethesda Academy and knew of our reason for being in the area. It was time well spent because Mr. Kemp who is a retired carpenter revealed how that skill was passed down to him through generations from an ancestor who was enslaved on Wormsloe Plantation. His research had also revealed that some of the enslaved skilled craftsmen from Wormsloe Plantation were rented out to places as far away as Charleston, SC to apply their skills. He told us that years ago he took a group of boy scouts out to an island in the area and they spent the night in some slave cabins that still existed at that time. Hearing him say that preserving extant slave dwellings was a good thing was very reassuring to me that the Slave Dwelling Project was necessary.

Upon entering the gate to Wormsloe, I set my eyes upon one of the most spectacular avenue of oaks that I had ever seen. The spectacular avenue of oaks at other places that I had spent nights in slave cabins like Evergreen Plantation in Edgard, Louisiana and Boone Hall Plantation in Mt. Pleasant, SC had nothing on Wormsloe for it stretched for what seemed like miles. Our host Sarah Ross, whose exuberance at the press conference the day before got us our place to stay for the night, met us on the property to give us a tour. She took us to the slave cabin which was a stark contrast to the tabby cabin we slept in the previous night on Ossabaw Island. It is a wooden structure that is currently used as a guest house so all of the modern amenities were included. This suited me quite well because in my 42 slave dwellings where I have slept, I have seen all extremes. For the intent of Tony Horwitz writing an article on the Slave Dwelling Project, something al little more raw would have been in order.

With darkness about to descend, the tour of the property was somewhat hasty, but boy was it spectacular. Contained on the property is the ruins of the oldest building in the state of Georgia, constructed of tabby and brick, it was explained how slaves from South Carolina were loaned/rented from South Carolina to help build the infrastructure for the Georgia’s early settlers. Sarah also showed us what was believed to be the slave burial ground on the site. It was amazing to hear Sarah explaining the intent of the owner and the Wormsloe Institute for Environmental History. In their effort to interpret the land scientifically and environmentally exists the opportunity to interpret the people that occupied the land, Native Americans, African Americans, and Europeans. That is what compelled her to respond to my plea at the press conference for a place to stay that fits the intent of the Slave Dwelling Project.

Over our dinner in the cabin of lowcountry boil that Sarah prepared for us, we learned that for us to stay in the cabin that night, two researchers had to find a room in a local hotel. That to me was a testament to the power of this project. I was thrilled Hanif Haynes was able to join us on the tour and stay for dinner for he will now be the local liaison between Wormsloe and the local African American community. Sleeping in a bed that night was much more comfortable than the experience the previous night in the tabby cabin on Ossabaw Island. Before leaving the next morning, I assured our host that because this stay was so impromptu, we have to plan another that will be more programmatic and beneficial to the intent of all entities but most of all get the local community especially African Americans more involved in what happens at Wormsloe.

Sweetfield of Eden Baptist Church

I have given the Slave Dwelling Project lecture in churches before, the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama and Mt Moriah Baptist Church in North Charleston, SC but they have always been at a time other than a regularly scheduled Sunday church service. Sweetfield of Eden Baptist Church in Pin Point, GA would be different for the presentation was given during the service from the pulpit and it was on Mother’s Day. After being instructed to show up at noon, my instincts got the best of me. Knowing that I had to leave shortly after the presentation, I convinced Toni Battle and Tony Horwitz that we should show up at 11:00 am because I was scheduled to present at noon. My incorrect assumption was that like my Baptist church, the service would start at 11:00 am. Well, showing up at 11:00 was far too early but it did give us time to take photographs outside of the church. When we entered the church there were a few youths conducting themselves in a noisy and disorderly fashion when one senior female came in and pulled out her switch and quickly restored order. As others began to gather, it was revealed to us that the lady who pulled out the switch to restore order is the mother of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

The presentation went well and as planned, we had to leave immediately after. Our attempt to find a place to have lunch in Savannah on Mother’s Day was met with failure when parking became a challenge so we gave up and drove back to Charleston. The drive gave Tony Horwitz great opportunity to go more in depth with me by asking questions about the Slave Dwelling Project for the article that he would be writing. We reached Charleston safely and being that it was Mother’s Day, after dropping Toni and Tony off at their hotels, I proceeded home to celebrate the occasion with my wife Vilarin and daughter Jocelyn.

Hinder Me Not ~ Sankofa Bound!

by Toni Renee Battle

On a bright Friday morning, Joseph McGill, founder of The Slave Dwelling Project, myself and Tony Horwitz, author and journalist, rolled down an oyster laden driveway blanketing the Pin Point Heritage Museum. We were minutes from Savannah, Georgia and were in the heart of a community named Pin Point, founded by former slaves of Ossabaw Island. As we exited the car, murals greeted us as we walked to the entrance of the museum. Entering the space we were greeted by black and white photos of black elders, representative of Pin Point’s history. The photos told a story of hard work, tradition and determination. Many residents of Pin Point, Georgia made a livelihood of crabbing and farming and shucking oysters at a regional factory.

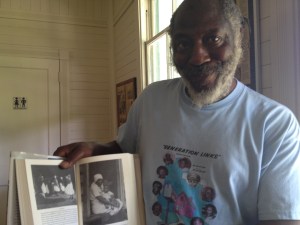

While browsing the photos, an older gentleman approached us and introduced himself as Hanif Haynes, a board member of the Museum and Ossabaw Foundation, and a descendant of Ossabaw Island. He immediately began sharing the oral tradition of storytelling by giving details of how the ancestors who were left on Ossabaw, following Emancipation, made a way for themselves and those who left Ossabaw eventually formed the community known today as Pin Point, Georgia.

As we listened, more and more people began arriving for the day’s press conference announcing collaboration between the Georgia Historical Society, Pin Center and Ossabaw Foundation. The honoring of this collaboration was The Slave Dwelling Project’s overnight stay on Ossabaw Island. While at the press conference, you heard from historians, community members and Ossabaw descendants speaking to this historical occasion and the importance of maintaining community voice in keeping Gullah-Geechee culture alive. Following the press conference, we found ourselves in numerous talking circles. Within these circles I was honored to meet many Keepers (grios maintaining culture, tradition and history).

Following the press conference, we headed to Bethesda School campus for a community luncheon before heading to the docks for Ossabaw. As we arrived at the docks, we were greeted by local Keeper, Patt Gunn. She would be joining us on Ossabaw to share in traditional Gullah storytelling. Additionally, our host, Paul Pressly (Ossabaw Foundation), Hanif Haynes (Ossabaw descendant and Foundation board member), Tania Smith-Jones (Administrator of Pin Point Heritage Museum) and Tony Horwitz (author and journalist) were part of the sojourn to Ossabaw Island.

The only way you can access Ossabaw Island is by boat. As the engine started, we all eagerly cheered as the boat lurched forward to ancestral lands. Haynes named off the names of other islands and sand bars as we passed by on our journey. He explained the importance of gauging the distance from the shoreline, otherwise one could end up stuck on a sandbar. After about twenty minutes, we slowly pulled up to the dock of Ossabaw Island. Upon arrival, you are greeted with a main sandy road which leads to the large big house, with a wrap-around porch.

Our small party, entered the big house and gathered in the main living room. Pressly provided us with a historical overview of Ossabaw; the island is originally the ancestral lands of the Creek and Cherokee Native Americans before being occupied by Europeans, who enslaved Africans and Natives to labor on four known plantations. During the 20th century, the West family purchased the island and during the 21st century sold Ossabaw to the state of Georgia as nature and educational preserve.

Gunn brought our gathering to life by engaging everyone in a traditional version of Gullah storytelling. She invited everyone to welcome the ancestors into the space and to celebrate their lives, traditions and customs during our time on the island. It was a fitting start to The Slave Dwelling Project’s overnight stay.

Following Gunn ending the welcome with a traditional spiritual, we embarked on our exploration of Ossabaw Island. Pressly announced we would walk to the slave quarters and then ride by truck to the center of the island, where one of the original plantations existed. As we exited the big house, Pressly stopped to show us an indigo plant. He explained, this plant was a descendant of the original plantation crop planted on Ossabaw.

Just beyond the indigo plants, Pressly stopped in front of a smokehouse built by the enslaved. The smokehouse was built with brick, wood and tabby materials. Tabby is made of a combination of oyster shells, lime and sand. It is a known building style used in parts of West Africa, that the enslaved brought to the Americas. The material is unique, strong and resistant to weather elements. We continued to walk a pathway from the smokehouse to a row of slave cabins. As we approached them, the group began to cease talking and instead stand in quiet reverence of the sacred space before us.

Right before we entered the cabin, a Sankofa bird circled and looked back at us. Haynes and Gunn immediately noticed and pointed to the sky. We all looked up and smiled, feeling the ancestors welcoming us to reclaiming the past and acknowledging their contributions to the history of the land (The concept of Sankofa comes from the Akan people of West Africa. It loosely translates to “go back and fetch what you forgot.” The deeper meaning encourages us to go back and revisit the past in order to move forward. We reach back to retrieve what our roots teach us, so that we can achieve our best in moving forward. The bird is symbolic of this belief, as it flies forward, while looking backward).

Pressly gave McGill the honors of opening the cabin door. As we entered the space, many of us stood in silence with a flurry of tears. You could feel the energy of pain, joy, anger and hope. The surrounding walls were made of tabby and wood. A brick fireplace divided the cabin into two separate quarters. We slowly exited the cabin to explore the rest of the island.

We climbed into the truck and traveled toward the center of Ossabaw. We travelled a main road lined with humongous oak trees lining either side of the road. Haynes explained that we were headed to what was known as Middleton Plantation, which was the plantation his direct ancestors were enslaved on. Upon arrival, we viewed the overgrown vines and some tabby slave cabins that were not structurally sound. Just beyond the yard sat a sandbar area with a tree dipping into the water. Haynes and I ventured beyond the group and stood in the wet sand and took in the reverence of the moment.

He shared that his ancestors farmed oysters on this very site as a means of survival post slavery. Haynes shared with our group that there had been a church on the island that the enslaved had named “Hinder Me Not.” These same men and women who were once slaves later made a home in a community that formed on the mainland of Savannah, Georgia that they named Pin Point. As he shared this story many of us looked at each other and smiled with pride and repeated, “Hinder Me Not!” Imagine how empowering that must have been? To have been a slave, become free and to then enter a place of worship called “Hinder Me Not.” Each time one would feel they could not go on, all they simply had to do was utter the name of the church. The very name of the church spoke to the very spirit of these ancestors that refused to allow any hindrance to block their freedom path.

Featured Gallery: Ossabaw Photos by Toni Renee Battle

no images were found

Pressly called out for our group to gather together quickly because we were being hosted for dinner by Mr. Roger, who was one of the caretakers of the island. We journeyed back towards the outskirts of the island and part of our party decided to walk towards Mr. Roger’s residence. We were met with true southern hospitality! Mr. Roger and his family had a home-cooked meal awaiting us and shared tall tales of his more than 30 years of residing on the island. It turns out that Mr. Roger is also a cook for former President Jimmy Carter! He travels from time to time to Plains, Georgia to personally cook for the Carter family. He is a true cowboy with a larger than life personality and a love for the land of Ossabaw Island.

Following dinner, we travelled back to the slave quarters to begin our overnight stay. McGill, myself and Horwitz were the only three to stay the night in the cabin. The rest of the group stayed in the big house about five minutes down the road. We all joined together to participate in a libation ceremony to honor our ancestors and those who had been enslaved on the land of Ossabaw Island. We also blessed the space and sang spirituals to pay homage to those who came before us. Following our ritual, we exited the cabin and were greeted by thousands of stars lighting the sky and our path. One group headed to the big house and the other group gathered belongings to lay down for the night. McGill, Horwitz and I made pallets and stretched out on the hardwood floor. We talked about race, slavery, war, Django (the movie) and ancestors. In particular, we discussed how as a slave on this island one would have truly had to be strategic to escape due to having to cross such a large waterway. McGill shared how Harriet Tubman had been known to have travelled this area of the Gullah Islands. Laying there, I thought about the untold stories of the ancestors who had laid their bodies within this same cabin. The ancestors who prayed and dreamed of a day their descendants would be free.

The next morning we awoke and stretched shortly after dawn. We reconnected with our group and shared about our experience of the overnight. Our group members were leaving and a second group were scheduled to join us within a few hours. We quickly freshened up and awaited the second group of visitors. This group had visitors from Boston, Atlanta, Savannah and other areas. Upon arrival, they were met with Gunn’s traditional storytelling and then we all shared lunch under the oak trees and headed back to the slave quarters. After McGill finished his historical overview, group members began heading back to the big house to get out of the heat. I noticed that the white group members headed immediately up the road, while the black group members took every opportunity to take photos and reluctantly kept revisiting the cabin.

Seven Shouts

It then struck me, at what time would there be almost ten black folks out of enslaved history, from different parts of the country, in the midst of a slave cabin with McGill, on Ossabaw Island? I gathered everyone and asked for us to stand in the cabin, in traditional circle format and pay homage.

We all immediately returned inside, circled up, held hands and bowed heads. I felt moved to pray and give thanks to the ancestors, others followed and Haynes began a traditional shout of ancestral energy. We all repeated seven shouts.

On the seventh round, I could no longer contain the overwhelming energy and gave into Spirit and shouted and cried. I began clapping, and others joined in. All of us began shuffling our feet and clapping our hands in a traditional ring shout. Our bodies moved in ancestral ways that our DNA could only know. The energy poured, lifted and shifted through the circle with grace, love and freeness. The power of our stomps hit the hardwood floors as our claps thundered a drum beat indicative of our ancestral lands. All of a sudden we all stopped, tears pouring down our faces in awe of the powerful experience we had just shared in the sacred space. As we walked out, many of us said how empowering the experience had been to acknowledge the culture in that celebratory way. We gathered in front of the slave cabin’s blue doorway. The enslaved painted and stained doorways with the color blue to protect against evil spirits. This door is also known as a “haint door.”

Sankofa Bound

By the end of the day, it was time to leave Ossabaw. As we walked the road leading to the docks, I kept looking back feeling a sense of loss. While on the water, I mentioned to Haynes that I heard him mention the name of “McAlpin” in part of the Ossabaw story. I shared that one of my ancestors was a McAlpin and our family had difficulty locating others. Haynes smiled and said, “Toni, you and Joseph are not saying goodbye to Ossabaw. Both of you will be back. You see that island over there? There’s a large group of McAlpins living there!” My mouth dropped. I responded, “WHAT?!” Haynes laughed and said, “This is the beginning of much work to do. The two of you are doing Sankofa! Your Ossabaw experience is Sankofa bound!”

Lest We Forget

by Toni Renee Battle

Joseph McGill, Founder of The Slave Dwelling Project, picked me up from the Charleston, South Carolina airport describing our upcoming overnight stay. Tony Horwitz, author and journalist, would join us the following day for our road trip to Savannah, Georgia and then a boat trip to Ossabaw Island (Gullah barrier island). McGill explained that Friday night we were scheduled to stay overnight on Ossabaw and possibly Saturday night. He said, “I’m not sure if Saturday night we will stay on Ossabaw, or if our host has found another plantation within the area where we may do a second stay. It’s all in the air right now.” I responded, “Joseph don’t worry, ancestors will direct us where we are supposed to be!” McGill laughed and looked over his glasses at me and said, “Toni, there you go!” I responded, “There you go! You know when we get together for a stay, ancestors always surprise us with a purpose. Why would this be any different?”

Ossabaw Island was going to be my third stay with The Slave Dwelling Project. October 2012, I had done two back-to-back stays at Bacon’s Castle (Surry, VA) and Sweet Briar College (Sweet Briar, VA). Both stays had been powerful and had huge community implications afterwards. Based upon our past stays, I was confident that we would be ancestrally directed for Saturday night. Where we needed to be would be revealed by Saturday morning.

The following day, we connected with Horwitz and hit the road to Savannah, Georgia! As we rode, Horwitz interviewed McGill and slowly began sharing his own personal story. The three of us swapped stories, laughed, and spoke about the impact of legacy to its descendants and to this country called the United States of America. We pulled into the oyster laden driveway of the Pin Point Historical Museum located in Pin Point, Georgia. We were attending a press conference to announce a regional collaboration of the museum, Ossabaw Island, Penn Center and the State of Georgia regarding preserving Gullah-Geechee culture. The Slave Dwelling Project overnight stay on Ossabaw Island was to commemorate this collaboration. We toured the museum which told the stories of descendants of the enslaved of Ossabaw Island whom, after Emancipation, started a community called Pin Point and worked in a regional oyster factory. While touring the museum, McGill and I met Hanif Haynes, a descendant of Ossabaw and a board member of the museum and the Ossabaw Foundation. He graciously shared oral tradition stories of the ancestors as we awaited the press conference to begin.

Eventually, Paul Pressly (Ossabaw Foundation), kicked off the press conference with lots of excitement of the meaning and impact of the collaboration. He then introduced McGill to speak to the celebration of The Slave Dwelling Project stay. McGill took the microphone and shared the importance of preserving slave dwellings and then said, “If there are any of you who are aware of additional locations within the area that will welcome us, we are seeking a Saturday night opportunity.” Following the press conference, a tall red-headed women immediately approached McGill. While they spoke, I ended up in two talking circles of Keepers (people who are Keepers of culture, tradition and histories of their people and/or cultural group) and community members.

Before embarking for Ossabaw, McGill excitedly called me over. He said, “Remember what you said in the car? Well we’ve been directed!” I said, “Uh?” McGill continued to explain that the tall red-headed woman I saw would be our Saturday night host. Her name was Sarah Ross and she had invited us to stay at the local Wormsloe Plantation. McGill continued, “Some folks view Wormsloe as one of the largest plantations in the state of Georgia.” My mouth fell open. My eyes filled with tears as McGill updated Horwitz of where we were being led to stay for Saturday night. As we walked, I thanked God and the ancestors for directing our path on this trip and wondered what our purpose would be when we encountered Wormsloe.

Friday night and Saturday we spent time on Ossabaw Island. That journey was beyond words of people we encountered and what we experienced while there. We departed Ossabaw by boat and headed back to the mainland of Savannah, Georgia. Hanif Haynes volunteered to guide us to Wormsloe Plantation, but asked if we could stop by an elder’s house who was directly descended from Wormsloe. McGill agreed and once in the car, we followed Haynes to our second night stay.

Haynes guided us to another community started by former slaves called Sand Fly. Within Sand Fly lived an elder named, Mr. Bess. Haynes requested permission for us to have wise counsel (meeting with an elder which involves traditional oral storytelling seeking information in a respectful and honoring way) with him. Bess agreed and we entered his home and settled into the living room. McGill spoke with him about our upcoming stay and our purpose in visiting the area. Bess began sharing that he was a direct descendant of the Wormsloe Plantation and that many of the enslaved had been master craftspeople. He explained that the plantation was massive and some of the enslaved had even traveled to Charleston, South Carolina because of being farmed out due to their high skill level. Many of the enslaved were carpenters, iron smiths, cooks, seamstresses, etc. Bess was descended from master carpenters. He showed us his fireplace mantle, which had intricate carvings displaying his ancestral skill. He explained that he had learned from two generations of elders and they had learned from generations before them. Majority of the generations had been enslaved. He said each family in community was known for a particular trade and/or craft which had been passed down since slavery.

We thanked him for his time and he encouraged us to return to the area in the future. Haynes then guided us to Wormsloe Plantation. We drove onto the main road which led to the big house. As we continued to drive, I realized we had been driving more than five minutes! The main road of the plantation was lined with over two hundred arching oak trees. Finally we arrived at the back side of the big house and McGill called Sarah Ross, President of the Wormsloe Institute for Environmental History and our host.

Ross drove up in a golf cart and encouraged us to follow her to the slave cabin. We followed and passed the plantation library and were in amazement of the mere size of the grounds. Eventually we arrived at a white cabin with red shutters. As we entered the space, it was obvious it had been majorly upgraded, yet still had remnants of its original use. The cabin was currently used as a cottage space for guests and scholars. Ross gave us a quick tour of the cabin which was divided into two separate spaces. She then told us she had cooked a Lowcountry Boil (shrimp, potatoes, corn, vegetables boiled with seasoning) for us, but first wanted to show us some of the plantation.

We followed her out to a golf cart and climbed onto the front and back. Ross drove for another good ten minutes and shared that the plantation itself covered thousands of acres. We stopped first at a mound of oyster shells which were evidence of the Cherokee’s ancestral footprint. We stopped at the side of the road and walked the land. I gave thanks to my Cherokee and Choctaw ancestors. Tears overwhelmed me as I thought of them and the history this space represented.

Ross looked at the sky and suggested we move forward before sundown. We continued on in our golf cart and stopped at a site that left us breathless. Ross said that we were viewing what used to be the original big house and was now ruins. All that remained was the outline of the foundation. Horwitz, McGill, Haynes and I stood in the space with our mouths open. The walls surrounding us were made of tabby! Tabby (a mixture of oyster shells, lime, clay and sand) was a building style found in West Africa, which the enslaved used to build structures in the local area of this country. Ross continued, “We’ve established that this is considered one of the oldest structures in the state of Georgia.” I began crying, Haynes rubbed my back and had tears and McGill and Horwitz quietly took in what was before us. We reverently walked to the wall and laid our hands on the tabby wall. Black and white hands laid hands on the proof that ancestors had been present.

I said to Ross, “Do you realize how significant this is? This is HUGE! We come from oral tradition which dominant culture consistently dismisses as NOT accurate. You’ve shared with us your work of documenting this plantation’s footprint which matches up with many oral stories Haynes and Bess have shared with us. YOU can be a bridge to the local black community trying to establish their roots!” Ross had tears in her eyes and said, “I know. I want to be a bridge. That’s part of why I reached out to The Slave Dwelling Project. We have the history here and are now obligated to be part of the change. We can do this!” I gave her a bear hug and said, “Sarah, thank you for being a cultural ally! You represent what is needed to engage the difficult conversations, but also the acknowledgement of this horrific history and the right way to flex privilege! We will support you.” Haynes confirmed that locally he would begin initiating a relationship with her to build a bridge.

Featured Gallery: Wormsloe Photos by Toni Renee Battle

no images were found

We walked the sacred space and hesitantly left and Ross shouted, “Oh! There’s one more place I need to take you to before sundown! How could I forget?” We drove on and stopped in front of an open area surrounded by a circle of trees. The air became quiet and the wind shifted. As we stepped out Ross announced, “I knew you would want to visit this space. This is the enslaved burial grounds.” Haynes, McGill, Horwitz and I all exchanged looks. Haynes, McGill and I immediately began walking the area. We cried, held our chests and kept turning around. I put my hands out over a depressed space. Haynes and McGill joined me and we circled up. We prayed, gave thanks to the ancestors and their sacrifice, we called out that they had not been forgotten. Additionally we honored the land our Native ancestors had walked and also died on. The wind picked up and kissed our faces. With tears on our cheeks we sought out Ross and Horwitz. Ross shared that the plantation had utilized new LiDar technology to discover the burial site. LiDar is able to x-ray more than four layers of earth by a military plane.

My head shot up. I looked at McGill and Haynes and said, “That’s part of our purpose here!” They looked at me confused. I quickly turned to Ross and continued, “Could this be done anywhere?” She said, “Yes, why?” I said, “Just two hours earlier on Ossabaw Island, Haynes had told our group that local community were still distressed about not being able to find the enslaved burial grounds on Ossabaw Island! Based on what you’re saying, this is now possible!” Ross shook her red hair, nodding in agreement. She said, “Yes it’s definitely possible. We could partner.” Haynes let out a joyful, “ASHE’!” He jumped in the air and we hugged at the magnitude of the moment and discovery. Horwitz responded with a “Wow!” McGill let out a breath and said, “Ancestors are just having their way, aren’t they?!” We laughed in agreement and headed back to the golf cart. I sang with joy on the back of the cart, giving thanks in traditional songs. Haynes joined in and we all enjoyed the peace which entered our souls.

We toured the plantation library and Ross gave us another piece of news. Wormsloe had been a plantation that owned its own steam mill for the crop of rice. Slaves actually operated the steam mill. Additionally, Wormsloe had also attempted to cultivate silk worms as an investment. Ross stated that this would have been overseen by the women of Wormsloe Plantation. This was information we had never heard of and slowly took in this new twist to the local history.

We ended our evening over the enjoyment of Ross’ cooking skills of the Lowcountry Boil. We circled up and talked for hours on the back porch of the slave cabin. We talked about the legacy of slavery, its impact and the current work at hand. We also appreciated what Ross represented. She was knowledgeable of the history, acknowledged the history and within her privilege of position, she was willing to take risks to be a change agent. She was open, honest of what she knew and most of all she knew in order to truly impact she needed community voice and support. Wormsloe was an open history book willing to revisit its history and create action around slavery’s footprint. I looked forward to what that future would look like with creating bridges with Pin Point and Sand Fly communities.

We ended the evening with returning inside the cabin. Ross headed to the big house, Haynes headed home and McGill, Horwitz and myself stayed to bed down for the night. Since the cabin was updated, we slept in twin beds and had a restroom. I paid homage to the ancestors through ritual and blessed the space. McGill and Horwitz fell asleep before me. I laid under my blankets and began to cry.

I thought of the fact that the following morning I would wake up in a slave cabin, on a plantation, on Mother’s Day. The mothers are what I went to sleep thinking about.The enslaved mothers who were my ancestors. The very image of being sold from your mother or child. The irony of my past and present history collided in that moment. I thought of how my great grandmother once told of her mother, who had been enslaved, saying to her, “You don’t know da pain of being sold off from a chile. You don’t know.”

At sunrise, those words came back to me. I prayed and asked God to give her spirit rest. I asked that all the mothers who were raped, birthed babies, auctioned off, torn apart from family have rest. That their spirits know that their descendants had survived and many of us were honoring who they were through our work and also through the act of remembering. Lest we forget. The act of remembrance is a powerful way to bear witness to pain, joy and to heal from generation to generation.

We awoke and ended our morning by attending Sweetfield of Eden Baptist Church in Pin Point, Georgia. We entered the church and awaited the Mother’s Day service to begin. As we quietly talked we were interrupted with, “Do I need to get my switch? Ya’ll know betta!” An elderly black woman jumped up from a church pew with a switch (twig from a tree) and shook the church as she stormed down the aisle to reprimand some disruptive teens. She came back and began sharing with McGill and I about a lesson her uncle had taught her when she was a rebellious youth. I chuckled and told her she had given me a flashback when she jumped up with that switch. I felt the sting of what the switch represented. She laughed and said, “It taught you a lesson. You remembered to mind ya elders!” I responded, “Yes Ma’m I did!” We settled back and a community member said, “Have you met Miss. Leola?” I answered we hadn’t formally, but informally she and I had enjoyed our cultural exchange of storytelling. She said, “Oh ok. You do know that’s Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’ mother?” McGill and I looked at each other and laughed for about five minutes at the irony of it. It was true. Miss. Leola was Thomas’ mother.

Horwitz came back to our occupied pew and said he was looking forward to a good black church experience. He said he enjoyed our traditional music and missed hearing it on a regular basis from some his earlier days of living in various communities. As devotion began, Horwitz was not disappointed. I sat back and drank my cup of spiritual food: call and response, shouting and soulful praise through song. We swayed, clapped, shouted and sang in Spirit! As my arms were held in the air, tears of joy came for the blessing of the experience I had shared on this journey with Horwitz and McGill. I was thankful for the act of remembrance and the ability to do so in a cultural way; in ways that my ancestors would have been punished for on many plantations. It was there in the sanctuary that I gave thanks of knowing and living the words of the ancestors… “Lest we forget.” My chant to them on the altar was, “You are not forgotten. We remember you with praise and honor.”

We are always given very interesting and informative accounts of your stays. Thanks for sharing these wonderful and provocative insights into your many slave-dwelling stays.

Rhoda Green, thank you for the thoughtful comment. You and friends are always welcome on a future stay.

Your account of these quests into these sacred, ancestral spaces is so moving and uplifting with great detail and emotion you put into them Toni Battle. The entire project is wonderful and inspiring for sure as it is a subject that I’ve been interested in since the early 1990’s when first becoming a mother.

I was so adamant about wanting to find out more about my children’s ancestral roots back to slavery and even possibly the mother land but no one living in their paternal family seemed to have any information back very far.

I now have family living in Georgia and when we fo for visits I try to visit different plantations always with the hope that I will find an actual, orginal, slave quarter structure still standing. The two closest plantations to my families areas do not have them..

These stories and accounts have given me so much information and hope in being able to fulfill my long time desire of having a physical place to show my children and now grandchildren, where their ancestors would have suffered and lived like.

Although their family has roots in Louisiana and Mississippi, I would like to at least see and take them to a representation of the enslaved people’s lives.

I’m very much wanting to find out more about any plantations in Louisiana or Mississippi though as that’s where their ancestors were at. I do not see either of those states represented on your list at the bottom though.. Do you in this project have any information about those state’s plantations I’m wondering??

Thank you in advance and God bless y’alls work!

Hi Tanya,

The SankofaGen Wiki is a great place to look for information on plantations in the slaveholding states. You can find them here: http://sankofagen.pbworks.com/w/page/14230533/FrontPage. I hope you do find some of your ancestors’ places of memory so you can take the young ones.

Blessings!

Toni